She fainted on Memorial Day, falling and breaking her jaw and several of her teeth. She came home from the hospital after that on TPN, IV nutrition. An old friend of mine agreed to take my mom's elderly dog for the rest of his life so he lives with her in Rhode Island now. He was just too much work for someone so ill.

She was on the TPN only a few days. Finally the doctors had hit upon the right combination of drugs to keep her from constantly vomiting. On that last day, my husband and I were there at 2 p.m. and she was eating some Italian ice. She said she felt a bit weak but she had her cane. She was hardly throwing up. She had a doctor's appointment in 2 days, to talk about putting in a feeding tube and a gastric drain (she was throwing up stomach bile, as it couldn't drain into her strangled intestines).

I came back at 7 p.m. to hook up the IV nutrition and found her dead--she had been in the middle of putting on her pajamas. From what I saw and what the paramedics who responded to my 911 call said, it seems like it was a sudden, instant, catastrophic event. Stroke, heart attack, blood clot? She did hit her head, but there was almost no blood. The medical examiner signed off without having to autopsy her so we'll never know for sure.

She was buried with my father's ashes, next to her parents and her mother's parents.

The eulogy I wrote:

When I was little, sometimes my parents would leave me at my grandparents’ house for the weekend. There, I’d get to sleep on a camp bed in the living room and the ghost of Mrs. Winters would tuck me in. The reason I slept in the living room is because that’s where the picture of my mom was. I’d be okay with my grandparents, until I saw that picture. Then I would realize my mom wasn’t there with me, and I would cry and cry and hug the frame. That’s how I feel now, every time I open Facebook and there’s my mom’s picture on my wall. The child of 40 years ago, that still lives in me, reacts: My mommy isn’t here! I want my mommy! Only now, there is no telephone to where she has gone. No reassurances that she’ll be here tomorrow and everything is okay. Because she won’t be here tomorrow and right now everything is not okay.

My mom had her moments, but mostly she was generous and kind. She adopted my friends as surrogate children. One of my friends asked her to make a very difficult cross stitch piece. It took her four months and all she asked for was that my friend buy the colors of embroidery floss she didn’t already have in her vast stash. Her house is filled with quilts of all sizes and colors, items she painted, embroidery, and more. She loved her little dog fiercely, even when his advancing age made him difficult to care for, and it broke her heart to send him to his new, final, forever home two weeks ago (where my friend is spoiling him and loving him for the rest of his life). Her cat was always with her in her last days, on her lap or curled up on the other end of the couch, just watching her. He lives with me now.

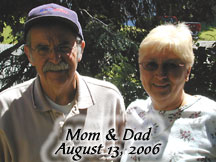

My father’s long illness was horrible for all of us, but she cared for him with dignity as long as she was able and mourned him fiercely when he finally left us forever. My grandma was a difficult woman, but my mom lived with her for years before her death and made sure she had everything she needed.

And somehow, in between caring for two sick people and making hundreds of quilts and cross-stitch pieces and painted pots, she read voraciously, swapping books with me and visiting the library almost daily as part of her long walks—up to ten miles a day when the weather was good. People would say, “I think I saw your mom walking…” somewhere across town and I’d say “Yup, probably.” She made many friends during those walks, people who also walked, and would join her on one leg of her journey.

That’s what we all are, in the end. We all walk alone, from birth to death, but people join us along the way. My mom’s path has diverged from ours, but who is to say that it won’t connect again, somewhere on the other side of time?

This is from King Edward VII’s eulogy:

Death is nothing at all. It does not count. I have only slipped away into the next room. Nothing has happened. Everything remains exactly as it was. I am I, and you are you, and the old life that we lived so fondly together is untouched, unchanged. Whatever we were to each other, that we are still. Call me by the old familiar name. Speak of me in the easy way which you always used. Put no difference into your tone. Wear no forced air of solemnity or sorrow. Laugh as we always laughed at the little jokes that we enjoyed together. Play, smile, think of me, pray for me. Let my name be ever the household word that it always was. Let it be spoken without an effort, without the ghost of a shadow upon it. Life means all that it ever meant. It is the same as it ever was. There is absolute and unbroken continuity. What is this death but a negligible accident? Why should I be out of mind because I am out of sight? I am but waiting for you, for an interval, somewhere very near, just round the corner. All is well. Nothing is hurt; nothing is lost. One brief moment and all will be as it was before. How we shall laugh at the trouble of parting when we meet again!

I keep wanting to tell her things, so I started a Tumblr where I can record the random things I want her to know.